Not Just a Faster Horse

Solving important types of problems faster than any competing system

Definitely Difficult; Probably Easy

There are many computational tasks important to both commerce and society which are deterministic in their definition, but which are difficult or impossible to solve using a single deterministic path of execution. Examples range from determining how proteins fold in pharmaceuticals research, to modeling radiation absorption in physics, or quantifying risk in finance.

There are other computational problems where you can easily describe the solution as a fixed and deterministic sequence of operations, but where you need to evaluate it across a range of possible inputs. Calculating how the natural variations in material properties might affect the strength of an aircraft component is one such example.

In both cases, the challenge is not just calculating an answer, but evaluating the system across a distribution of probabilities.

The Status Quo

The standard approach for solving these two very different problem types involves a brute-force three-step process: Randomly generate input data based on the anticipated probability distribution of those inputs (the sampling step), compute the output (the evaluation step), and repeat this process thousands or millions of times. Finally, you statistically analyze the resulting massive dataset to extract a solution (the statistical analysis step). Because of its reliance on distributions of random numbers, the procedure is called the Monte Carlo method. It dates back to the Second World War and the Manhattan Project, where it was developed to allow scientists to solve certain classes of problems that could not be easily solved any other way. It is deceptively simple (but compute-intensive) and is still widely used today.

As a central part of their operations, investment banks run nightly calculations of the risk of losses for their different financial products and these calculations use Monte Carlo methods running on dedicated on-premises clusters of computers. The recurring costs associated with such compute infrastructure can be tens to hundreds of millions of dollars per year for large banks. Similarly, aerospace firms deploy significant compute infrastructure (often in the cloud) for engineering simulations central to their operational needs.

To scale up their operations, organizations using these methods therefore need to deploy ever larger computing resources. And to achieve more accurate results, they must run Monte Carlo computations with ever more samples. But the quality of the solutions using this sample-evaluate-analyze approach yields diminishing returns as you increase the number of samples. Because of the sheer amount of compute hardware installation space and maintenance that would be needed, many investment banks today cannot scale their on-premises compute infrastructure as large as they would like to, despite having the financial resources to do so. Even if you can afford to buy a million horses, they will never be a replacement for an aircraft.

A Better Way

Unlike traditional computing systems which need software to explicitly implement the sample-evaluate-analyze process, Signaloid's UxHw technology allows a single execution of a program to evaluate a distribution of inputs and output a distribution result. Because it can be implemented inside a processor or provided as a virtual processor abstraction, UxHw (pronounced "u-x-hardware") is easy to adopt and makes it easier to implement many important computing workloads, compared to running on traditional computing platforms.

UxHw is a family of techniques we have developed (with over 90 intellectual property filings). It can represent arbitrary probability density functions using a small number of bits, with each representation instance occurring during a computation using that fixed number of bits in an instance-adaptive and provably near-optimal way.

UxHw defines how these distributions combine during arithmetic operations, keeps track of correlations as they occur, and provides mechanisms for statistical operations and Bayesian inference on these distributions. UxHw does not rely on sampling, and its representation quality improves linearly with representation size, whereas Monte Carlo improves only as the square root of the number of samples (i.e., you need to put in 100x more effort to get a 10x improvement). These characteristics together allow UxHw to achieve fundamentally better performance than the status quo.

When applied to real applications such as sensitivity analysis of present-value computations and value-at-risk computation in quantitative finance, UxHw today can achieve speedups of over 1000-fold compared to running on today's highest-end processors.

Use It In Production

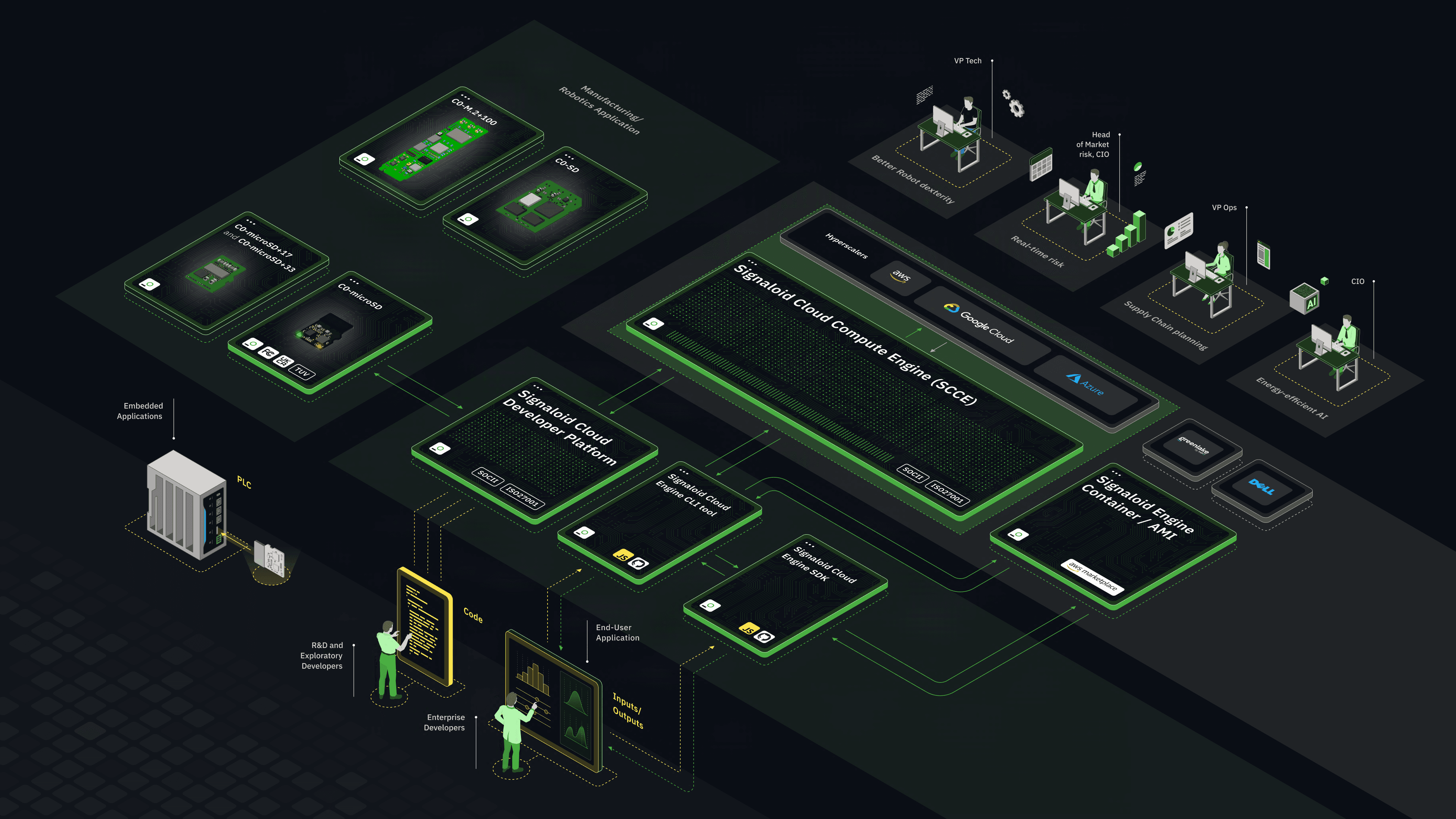

We've implemented UxHw so that you can deploy it in different forms: As a cloud-based computing platform, as an on-premises computing platform, or as hardware modules that augment traditional computing systems with UxHw technology. It's not just a faster horse: It's a fundamentally new way of solving a large class of important computing problems, and you can learn more about how it works by trying it out yourself today.